01 Dec Lactate threshold: Feel the burn!

Todd Buckingham, Ph.D. | Lead Exercise Physiologist, Mary Free Bed Sports Rehabilitation

Lactate has built up a pretty bad reputation in the past. Well, I’m here to dispel that reputation and give lactate the credit it deserves…I’m the hype man lactate never knew it needed!

First of all, lactate vs. lactic acid. I’m not going to get into the super sciency stuff because…well, frankly, you don’t care! Our body produces lactate not lactic acid, but they are used interchangeably among athletes (even though they shouldn’t be). For our purposes, I’m going to call it lactate, though, because…well that’s what it is! Haha. If you’re interested in understanding the difference between the two, drop me a message and I’ll be happy to differentiate!

Now that we have that taken care of, let’s talk about lactate. Lactate isn’t this terrible thing that hurts your performance like we may have been led to believe. Lactate is actually a fuel source that our bodies can use. In fact, you’re producing lactate right now as you read this! Lactate is produced during metabolism and shuttled to the liver where it’s converted to glucose so we can use it for energy (the science nerds will like to know this is called gluconeogenesis). However, when the exercise gets too hard, lactate can’t be transformed into glucose as quickly (the shuttle takes a long time) and it starts accumulating in the blood. This is when we get that burning sensation in our muscles. But contrary to popular belief, the burning sensation is not because of the lactate. It’s actually caused by hydrogen ions that are associated with lactate (if we remember back to chemistry class, more hydrogen ions in a solution cause the solution to become more acidic. i.e., our blood becomes more acidic and we get that burning sensation).

This point when lactate production exceeds clearance is called the lactate threshold (LT). Your LT is the fastest speed/pace you can swim/bike/run without having lactate build up in the blood. For beginners, LT pace is typically 10-15 seconds slower than 5k pace. For more advanced athletes, LT pace is about 1 hour or half-marathon pace. This means it isn’t a gut-busting effort but more of a slow, steady, gradual burn. It’s that “redline” that you ride for as long as possible before your body says, “enough is enough”. This applies to swimming, biking, running, rowing, and even hand-stand walking (if you wanted to do such a thing).

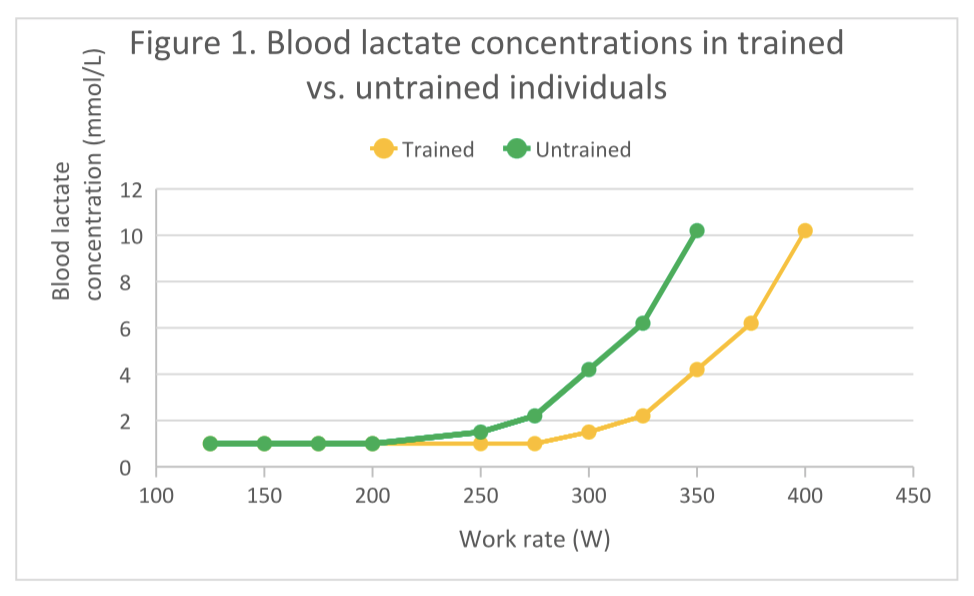

For untrained individuals, the LT typically occurs around 50-60% of VO2max. For recreationally trained individuals, LT can occur around 65-80% of VO2max. In elite endurance athletes, LT values can occur around 85-95% of VO2max. And much like VO2max, your LT changes throughout the season as you get fitter. As you can see in Figure 1, the higher percentage of VO2max that the lactate threshold occurs, the faster an individual will be able to swim/bike/run for a longer period of time.

If VO2max is your engine, think of the LT as your restrictor plate. It limits the amount of power or speed you can maintain for an extended period of time. So, if you have a high VO2max but your LT occurs at 50% of that max, the high VO2max won’t do you any good. This is why the person with the highest VO2max doesn’t always win the race.

The LT is measured by drawing blood from your fingertip at intervals during an incremental exercise test. This can be performed on a treadmill or stationary bicycle (or even swim flume if you have the access to one). You will exercise at an intensity that is increased every 3-4 minutes until you reach just beyond your lactate threshold. The benefit of testing in the lab is that you get an actual measure of blood lactate instead of an estimation.

Speaking of estimations…there have been a lot of field tests that have been developed to estimate the LT. However, these are estimations. You cannot get a true measure of lactate unless…you truly measure lactate! Sometimes these estimates can be accurate, but sometimes they can be off by a significant amount. Fellow Fly, Dave DaPrato, wrote about his LT experience here in the Performance Lab at Mary Free Bed. After performing a LT test on the bike and scoring 30W lower than what he thought he might get, he said, “…I am here to tell you that it is far more worth the money to have LT clinically analyzed.” If you want to read about his experience, take a look here 🡪 https://www.facebook.com/david.daprato.1/posts/10220174194517432

So why is understanding LT important? If you read Dave’s story, you will see that he had been training too hard based on the estimation of his LT. Tempo workouts felt like threshold, recovery rides felt strangely difficult, and he wasn’t recovering like he knew he should have been. Dave was experiencing a case of overtraining. I really like what he wrote at the end of his post because it resonates with me as an exercise physiologist and seeing this far too often. He said, “We may think our bodies can handle it, or we may justify that mind over matter hogwash, but I am here to say that the physiology of the human body cannot be fooled or cheated.”

Test. Don’t guess.

Oh! And one more thing…Once we stop exercise, our blood lactate levels return to normal fairly quickly – typically within one hour if you just sit down and even faster if you perform a dynamic cool down or walk. So, don’t believe the hype that compression boots, socks, or lifting your legs up against the wall while lying on your back will help clear lactate more quickly because it’s just not true. This is one of my biggest pet peeves. And when people talk about “clearing lactate” out of the muscles in the day or two after a workout, that’s even more untrue. Lactate doesn’t make your muscles sore. It’s the tiny microscopic tears in your muscle fibers that create delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS). That’s why your legs are sore a day or two after your workout. Because your muscle fibers are healing themselves. Not because lactate is still in your muscles. Okay, time to step off my soapbox now 😉